The gut bacteria test that gives you insight into your health

- Microbiome test kit

- 16S analysis

- Scientific insights

Learn more

about the microbiota

Last modified: 13-05-2025

If you occasionally have gurgling intestines and watery diarrhea, there’s not necessarily anything wrong with you or your stomach. But if acute diarrhea occurs regularly, there might be more going on. On this page you will read:

Diarrhea is watery stool that often has a different color and smell. With diarrhea, you need to go to the toilet three or more times a day for a bowel movement. Diarrhea is also called the runs.

There are two types of diarrhea: short-term (acute) or long-term (chronic) diarrhea. Acute diarrhea usually lasts a few hours to a few days. If the diarrhea lasts longer than two weeks, it is considered chronic diarrhea – even if the diarrhea comes and goes. The difference between the two lies in the cause.

Watch out for bloody diarrhea!

Bloody diarrhea occurs in severe gastrointestinal inflammation or infection. In this case, you should contact your doctor and antimicrobial treatment in the hospital is needed. It’s not a good time to do a microbiome test, because your microbiome is probably different from how it normally looks.

The difference between acute and chronic diarrhea lies in the cause. Acute diarrhea can be caused by an infection with a bacterium, virus, or parasite: these microbes cause an infection in the gastrointestinal tract.

When your intestinal mucosal barrier is too weak, it cannot properly absorb nutrients from the intestines. This may eventually lead to inflammation of the intestine.

Chronic diarrhea can be caused by a disease or condition in the gastrointestinal tract. Examples include ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Diarrhea can also be caused by persistent infections, for example due to a high number of unwanted bacteria that cause irritation (diarrhea).

Other possible causes of chronic diarrhea are:

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome;

- Food intolerances;

- Celiac disease;

- Medications;

- Stress;

- Antibiotic use;

- Accelerated metabolism;

In this article we mainly focus on acute diarrhea with a bacterial cause.

Acute diarrhea can occur from eating food or drinking water contaminated with a pathogenic bacterium. Raw meat contains bacteria that can make people sick. You only get sick if the meat is not properly cooked, has been left out of the refrigerator too long, or if utensils that touched the raw meat were reused (cross-contamination).

Bacteria in raw meat that can cause diarrhea include Campylobacter and Salmonella. These bacteria are sometimes also found in eggs, raw (unpasteurized) milk, and fish.

Your diet can also be a cause of acute diarrhea. If you consistently eat little fiber-rich food, the beneficial bacteria become undernourished, which can lead to watery stools.

Fiber supports healthy bowel function by absorbing moisture from the stool, resulting in firm and smooth stools. Fiber is found in vegetables, fruits, legumes, potatoes, and whole grain pasta and rice.

There are different types of fiber: soluble and insoluble. Each type feeds different gut bacteria. In the microbiome report you can read which of these bacteria are present in too high or too low amounts, and which (fiber-rich) foods can help rebalance them to relieve or prevent acute diarrhea.

In addition to fiber-rich food, it is important to drink enough water. Fiber needs water to swell; only then are they a suitable food source for your gut bacteria. So if you start eating more fiber, make sure you also drink more water. Without enough water, fibers won’t swell, which can lead to abdominal complaints (diarrhea or constipation).

There are several bacteria known to cause intestinal issues like diarrhea. These include Clostridioides difficile and Clostridium perfringens. These bacteria naturally occur in our intestines, where they don’t necessarily cause problems. Only when they are present in excessive numbers (for example after an antibiotic course) can they cause troublesome symptoms such as diarrhea.

Also, Salmonella, Helicobacter pylori and E. coli are known bacteria (proteobacteria) that can cause diarrhea. These bacteria occur in raw meat, milk, and eggs. Eating contaminated food can result in food poisoning.

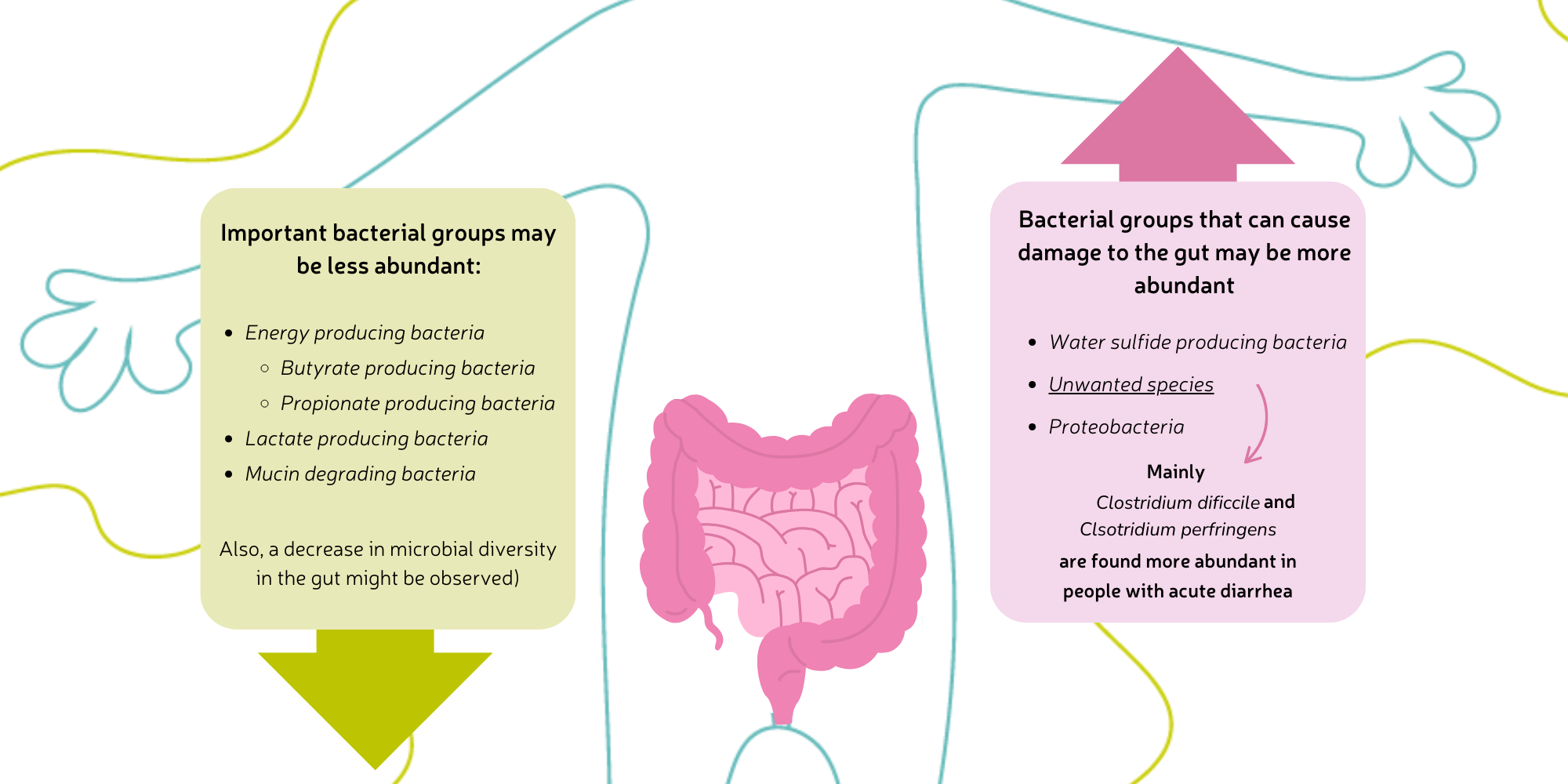

When you suffer from (acute) diarrhea, the composition of your gut microbiome changes significantly. Some bacteria start growing more rapidly, while others grow less. The image below illustrates this:

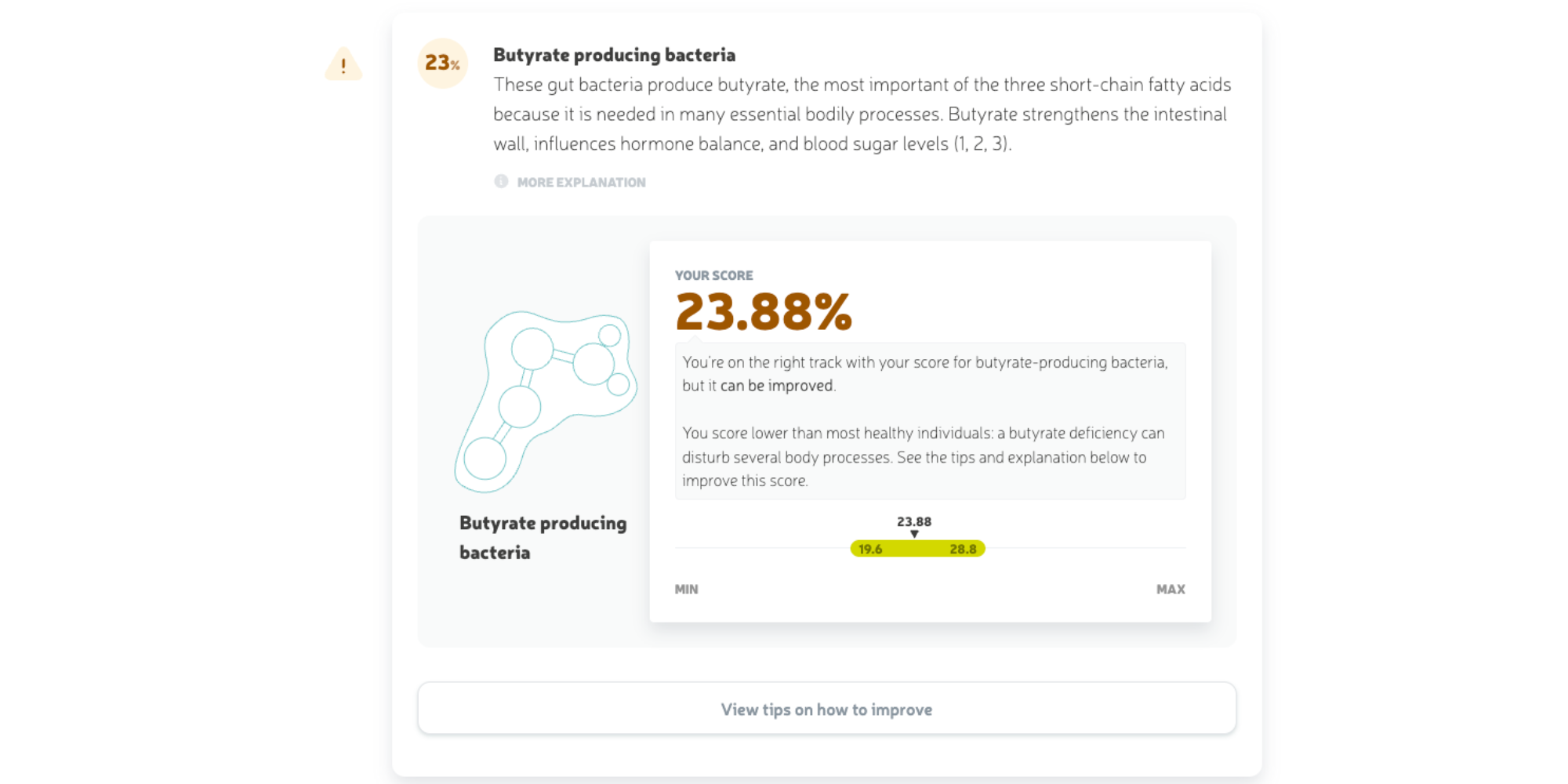

Scientific research shows that beneficial bacteria are less present in the gut during acute diarrhea. These include energy-, lactate- and butyrate-producing bacteria. At the same time, more unwanted bacteria are present. These are types that can be harmful when they overgrow. Think of C. perfringens and proteobacteria.

A disruption of the microbiome can cause diarrhea in various ways, depending on which bacteria increase or decrease. For example, if the number of butyrate-producing bacteria drops, less butyrate is produced. Butyrate stimulates water and salt absorption in the colon; a deficiency means less water is absorbed. This leads to more fluid remaining in the digestive tract, which is then expelled as stool.

For bacteria such as C. difficile, this process works differently. These infectious bacteria release harmful substances – so-called enterotoxins – that damage intestinal cells. The intestinal wall responds strongly ("help, an intruder!") and tries to flush out the intruder with water as a defense mechanism.

Do you regularly suffer from acute diarrhea? A microbiome test can help you identify the cause. After taking the home test, you’ll receive a clear report within four weeks showing which gut bacteria are present in high or low quantities. It also shows whether there are pathogenic bacteria that could explain your symptoms. This way you’ll know exactly who lives in your gut, and you can adjust your diet and/or lifestyle more specifically to address diarrhea.

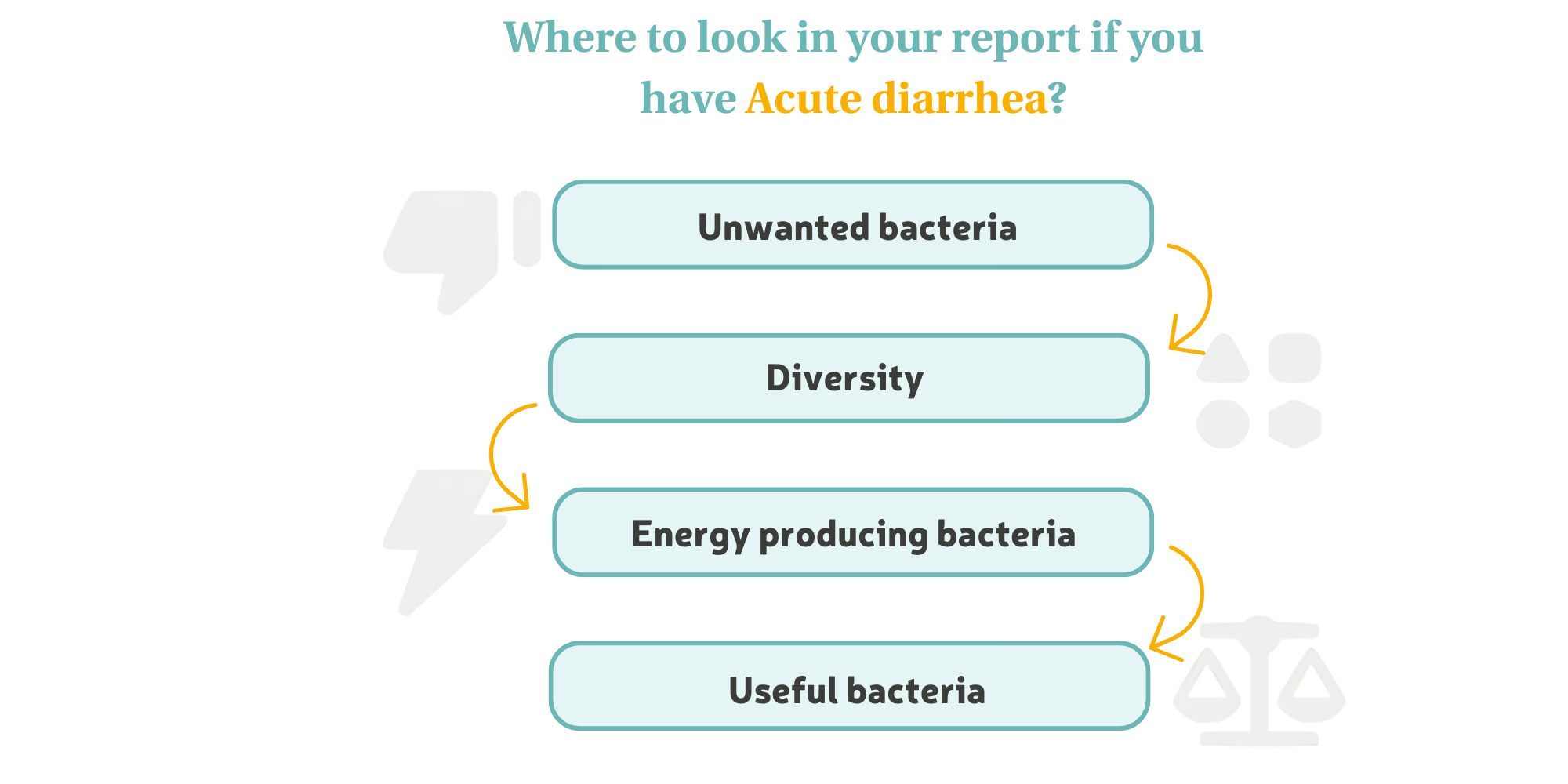

After you’ve done a microbiome test, you’ll receive a clear results report that explains your gut health step-by-step. The report is built around four main scores. The order of these is based on what usually affects gut health the most. If you’re dealing with acute diarrhea, we recommend reading the report in a different order, since different bacteria are more important here.

For everyone: always read the summary and improvement tips first.

We give practical tips for every pink and orange score to help make your microbiome healthier. If you’ve got a green score, we explain how to keep it that way.

Next, read the report in this order:

Proteobacteria naturally occur in the gut. They’re often useful and help with digestion and the immune system. In small amounts, they’re not harmful. But after things like a flu, they can multiply quickly and cause inflammation. This can mess with digestion and bowel movements, sometimes leading to diarrhea. Examples include E. coli, Helicobacter pylori and Salmonella.

Gut bacteria constantly produce gases like hydrogen. Hydrogen gas is useful and fuels other bacteria like those producing methane and hydrogen sulfide. But too much hydrogen can lead to too much of those gases, and that can cause diarrhea.

There are certain types of bacteria known for causing gut problems and nasty symptoms like diarrhea. These include Bilophila wadsworthia, C. difficile, C. perfringens, Enterobacter and Fusobacterium. In the report we call them "specific types." We highlight two of them here because they’re often linked to diarrhea.

C. difficile and C. perfringens can both naturally live in your microbiome. They make toxic spores that can survive in your gut for months. C. difficile often grows after antibiotics, increasing the number of spores and causing C. difficile infection (CDI), which is a serious gut inflammation. Symptoms can include diarrhea, fever, and stomach pain.

High scores for proteobacteria, hydrogen-producing bacteria and specific types may be the reason for your diarrhea. Ideally, these scores should be low (green). In the report, we give practical tips on how to reduce them if they’re high (pink or orange).

A diverse microbiome (green) means lots of different bacterial types are present. They work together to support important functions. This makes you more resistant to pathogens and less likely to get gut issues like diarrhea. With a less diverse microbiome (pink or orange), you may develop an imbalance where good bacteria don't grow well and bad ones can take over, messing up digestion and bowel movements.

Some gut bacteria produce useful energy substances while breaking down fibers from food. These include butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Enough butyrate is super important (green) for a healthy gut. It protects the mucus layer over the gut lining. A strong gut wall lowers the risk of inflammation. If the layer is weak (due to low butyrate – pink or orange), bad bacteria can reach the gut lining more easily and cause irritation, which affects digestion and stool.

There are loads of beneficial gut bacteria, each with their own important job. In the report, we cover 14 useful bacteria or bacterial groups. Even though they’re important, low levels of these bacteria (pink or orange scores) are not directly linked to diarrhea. That’s why more focus is given to the scores discussed earlier.

Still, it’s important to have enough beneficial bacteria (green score), because they contribute to a diverse and balanced microbiome. Plus, these good bacteria can suppress the growth and activity of unwanted ones. A good example: bacteria that make lactic acid (lactate). Lactate makes your gut slightly more acidic, which helps good bacteria thrive and holds back the bad ones.

Acute diarrhea is super annoying and never comes at the right time. Totally understandable that you want to get rid of it. But remedies like cola and chips haven’t been proven to work.

If you just have watery diarrhea and a rumbling stomach once in a while, it doesn’t necessarily mean something’s wrong. But if acute diarrhea keeps coming back, there might be more going on. A microbiome test gives you really valuable info to understand how your gut bacteria affect your health and cause gut issues. On this page you can read how the test works and whether it’s right for you.

Sources:

Dickinson, B., & Surawicz, C. M. (2014). Infectious diarrhea: an overview. Current gastroenterology reports, 16, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-014-0399-8

Generoso, Simone de Vasconcelos; Lages, Priscilla Ceci; Correia, Maria Isabel T.D.. Fiber, prebiotics, and diarrhea: what, why, when and how. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 19(5):p 388–393, September 2016. | https://doi.org/10.1097/mco.0000000000000311

Gupta, A., Singh, V., & Mani, I. (2022). Dysbiosis of human microbiome and infectious diseases. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 192(1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2022.06.016

Iancu, M. A., Profir, M., Roșu, O. A., Ionescu, R. F., Cretoiu, S. M., & Gaspar, B. S. (2023). Revisiting the intestinal microbiome and its role in diarrhea and constipation. Microorganisms, 11(9), 2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11092177

Larsen, O. F. A., & Claassen, E. (2018). The mechanistic link between health and gut microbiota diversity. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20141-6

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K., & Knight, R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature, 489(7415), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11550

Li, Y., Xia, S., Jiang, X., Feng, C., Gong, S., Ma, J., ... & Yin, Y. (2021). Gut microbiota and diarrhea: an updated review. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 11, 625210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.625210

MDL Fonds. (2025, March 31). I have diarrhea | MDL Fonds. https://mdlfonds.nl/klachten/diarree

Ramamurthy, T., Kumari, S., & Ghosh, A. (2022). Diarrheal disease and gut microbiome. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 192(1), 149–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2022.08.002

The, H. C., & Le, S. N. H. (2022). Dynamic of the human gut microbiome under infectious diarrhea. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 66, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2022.01.006

KvK nummer: 65867637

Website door: Ratio Design

This website uses essential cookies to ensure correct functionality. In order to improve our site we can also use optional cookies.

More information