The gut bacteria test that gives you insight into your health

- Microbiome test kit

- 16S analysis

- Scientific insights

Learn more

about the microbiota

Last edited 27-2-2025

You have become interested in the health of your microbiome. Perhaps you are experiencing digestive issues, IBS, or you simply want to improve your overall health. With a microbiome test, you will get a complete insight into what your microbiome looks like. In this article, we describe what a healthy and less healthy microbiome looks like. The distribution on this page is the same as the report with the test results:

Finally, you will also find in the report which enterotype you have.

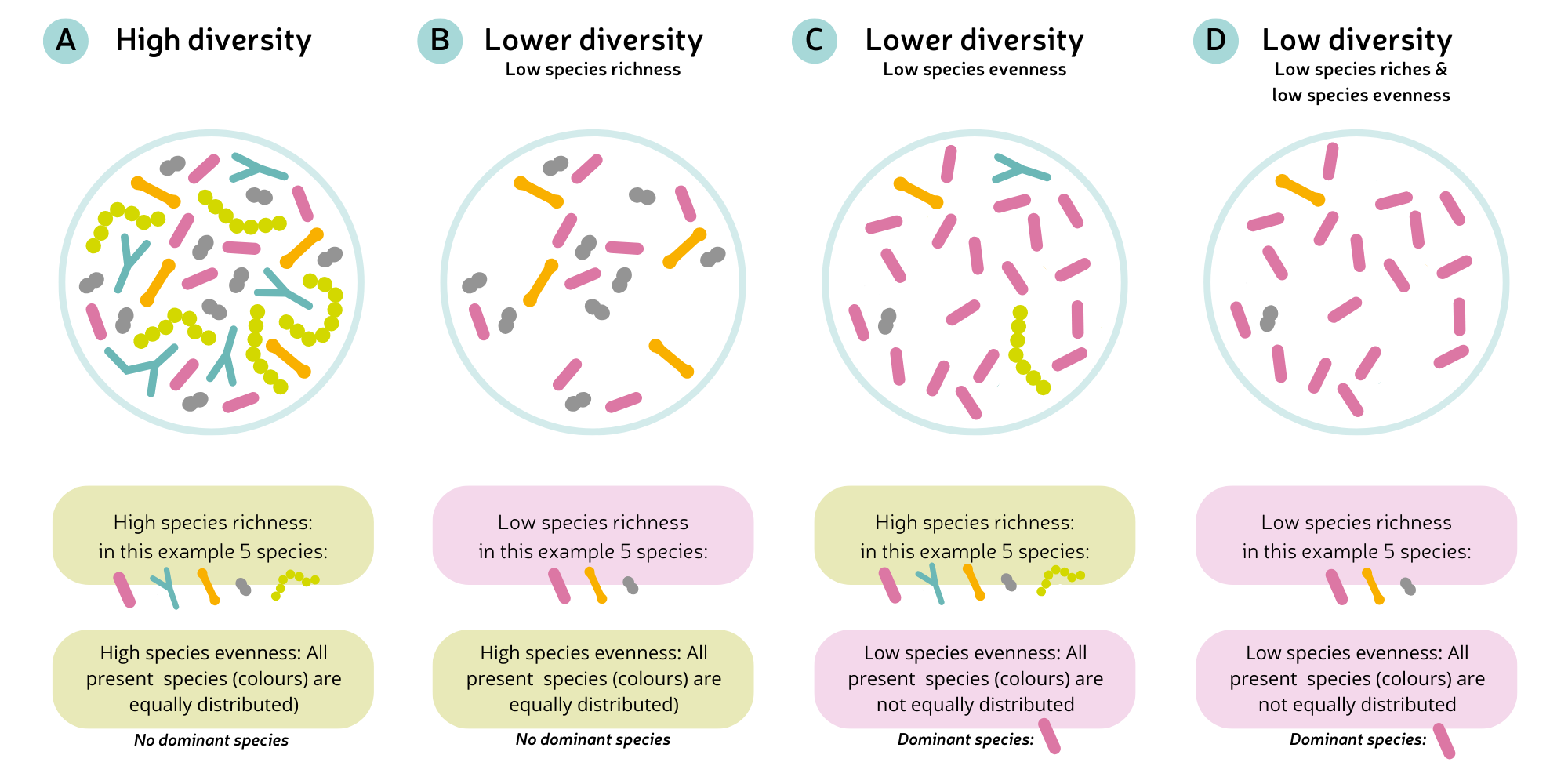

A diverse and balanced microbiota means there is a lot of variation in bacterial species. There are two factors that determine this: the bacterial species distribution and the bacterial species richness.

By species distribution, we mean the ratio of different bacterial species. The better the ratio, the more balanced your microbiota is. By species richness, we mean the number of different bacterial species. The more species that live in your microbiota, the higher the diversity is:

Four different situations of diversity in the microbiota. Each color represents a different bacterial species. On the left, you see an optimal diversity of a microbiota: many different bacterial species live in equal proportions, without one species dominating (A). In a lower species richness, fewer species live, but still in equal proportions. No bacteria dominate (B). In a lower species distribution, many different species live, but in unequal proportions. The pink bacterium dominates (C). On the right, both species richness and distribution are low: few species live, and in unequal proportions. You can see that the pink bacterium dominates (D).

You can think of the microbiome as a rainforest: trees and plants work together to form a thriving ecosystem. If many different types of greenery are present, that ecosystem flourishes (healthy). But if only a few trees grow, the ecosystem becomes one-sided, and it is not resilient in extreme weather conditions (drought, cold, storms). The same applies to your microbiome: if only a few bacterial species grow, you have a one-sided microbiota. But if many different species live in equal proportions, diversity is high, and balance is good. You can replace the extreme weather conditions with diseases or an antibiotic course.

When many species grow in your gut, there will also be enough to perform many different useful functions—and thus maintain your (gut) health. Scientific research shows that a diverse microbiota lowers the risk of conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). And low diversity has been associated with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

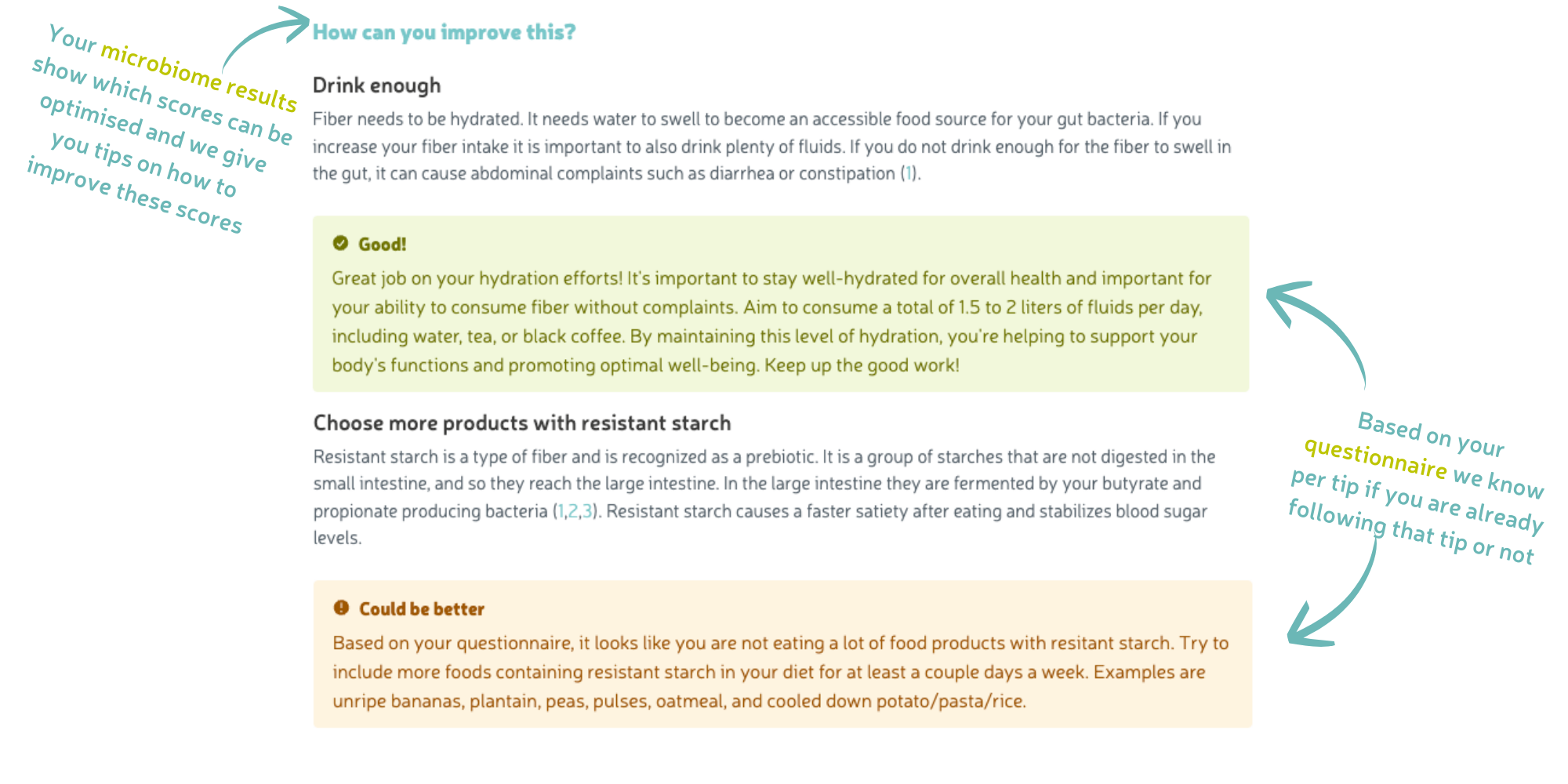

What will I see in my test results?

In your report, you will receive a diversity score with explanations and tips. The diversity score is based on how good your species distribution and richness are. A healthy microbiome is diverse, with many different bacterial species in equal proportions! If you have low diversity, there may be an imbalance in your microbiome. You will receive explanations and guidelines for diet and lifestyle to improve this score.

In the large intestine, gut bacteria ferment dietary fibers. In this process, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are produced, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs serve as an energy source for other bacteria and are extremely important for many different body processes. The bacteria that produce these SCFAs are called energy-producing bacteria and can be divided into 1) butyrate-producing, 2) propionate-producing, and 3) acetate-producing bacteria.

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is a common butyrate-producing bacterium. The butyrate it produces strengthens the intestinal wall, reduces inflammation, and promotes our immune system. To perform its function properly, it is important that F. prausnitzii receives enough dietary fiber.

Akkermansia muciniphila is a propionate-producing bacterium. The production of propionate happens indirectly: A. muciniphila first converts the mucus (mucin) from the intestinal wall into acetate. Acetate is then converted by other gut bacteria into propionate, which serves as an energy source and contributes to sugar metabolism and regulating satiety after eating. Only with sufficient mucin in the gut can A. muciniphila function optimally. The dietary fiber inulin is a prebiotic that strengthens the intestinal wall and mucus layer and indirectly stimulates mucin production. The more mucin available for A. muciniphila, the more propionate (energy) will be produced.

Almost all gut bacteria produce the fatty acid acetate, so you will not likely develop a deficiency of these bacteria. Therefore, we will not go into acetate-producing bacteria in the report.

What will I see in my test results?

In your report, you will see the scores for the amount of butyrate- and propionate-producing bacteria. A healthy microbiome has high scores in both groups (without worsening your diversity). Low scores for energy-producing bacteria can eventually lead to intestinal inflammation or a disrupted blood sugar level.

For both, you will also see how well your diet or lifestyle currently supports the growth of these two types. You will receive guidance to improve the scores if needed.

Bacteria are not necessarily 'good' or 'bad', but rather 'useful' or 'unwanted'. Some bacteria can play a role in health problems and are considered unwanted if they are overly present. These include 1) hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria, 2) proteobacteria, and 3) 5 specific species associated with diseases.

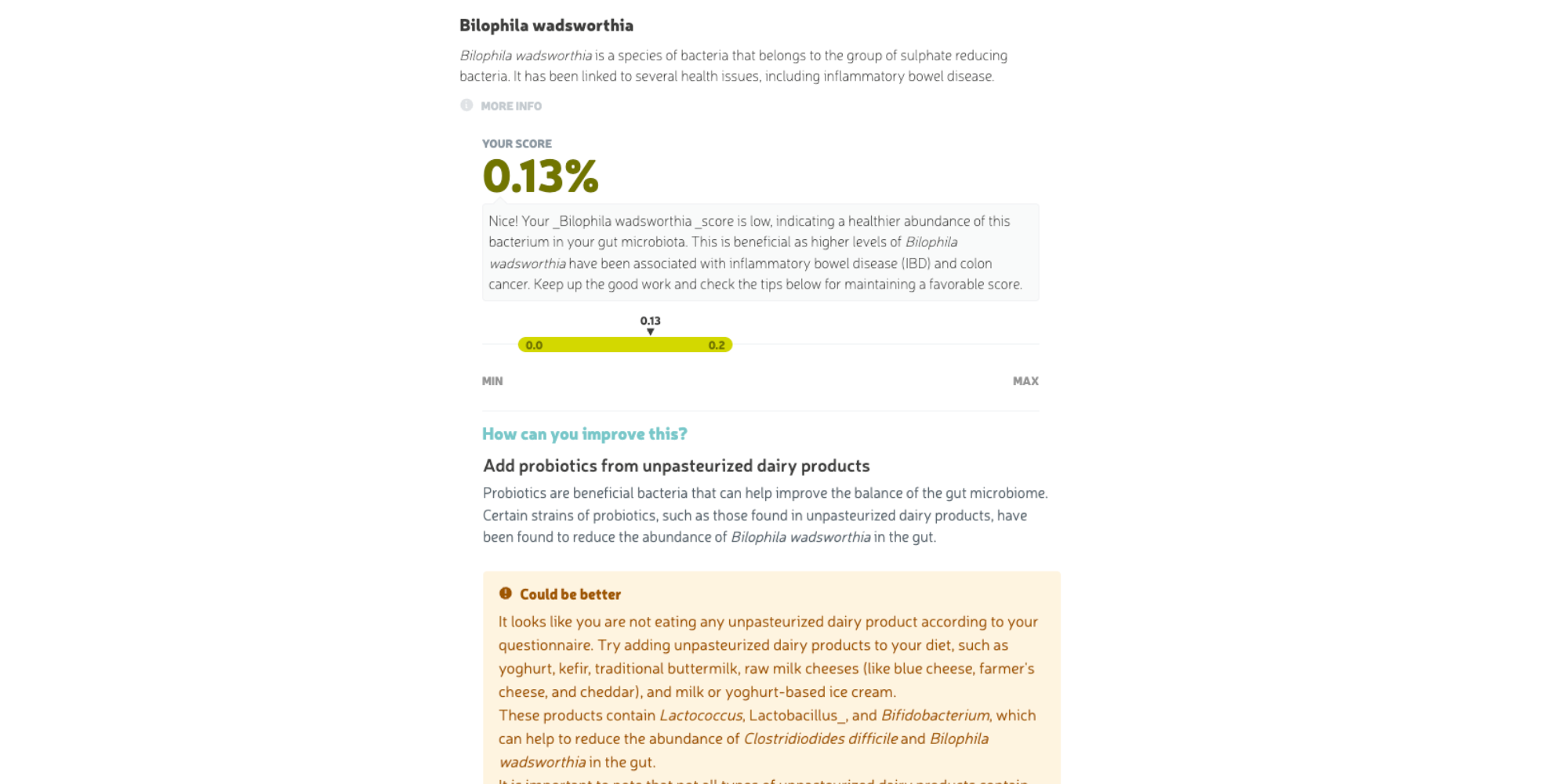

Hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria convert sulfate into hydrogen sulfide, a gas that naturally occurs in the intestines. Although this gas is useful, an excess can lead to inflammation and intestinal diseases. An overgrowth of sulfate-reducing bacteria such as Bilophila wadsworthia or Desulfovibrio can cause unpleasant conditions (such as inflammatory bowel diseases).

Proteobacteria form a large and diverse group of bacteria. When present in excess, proteobacteria can eventually cause inflammation. A well-known bacterium from this group is Escherichia coli, which can cause diarrhea and digestive problems when present in high numbers.

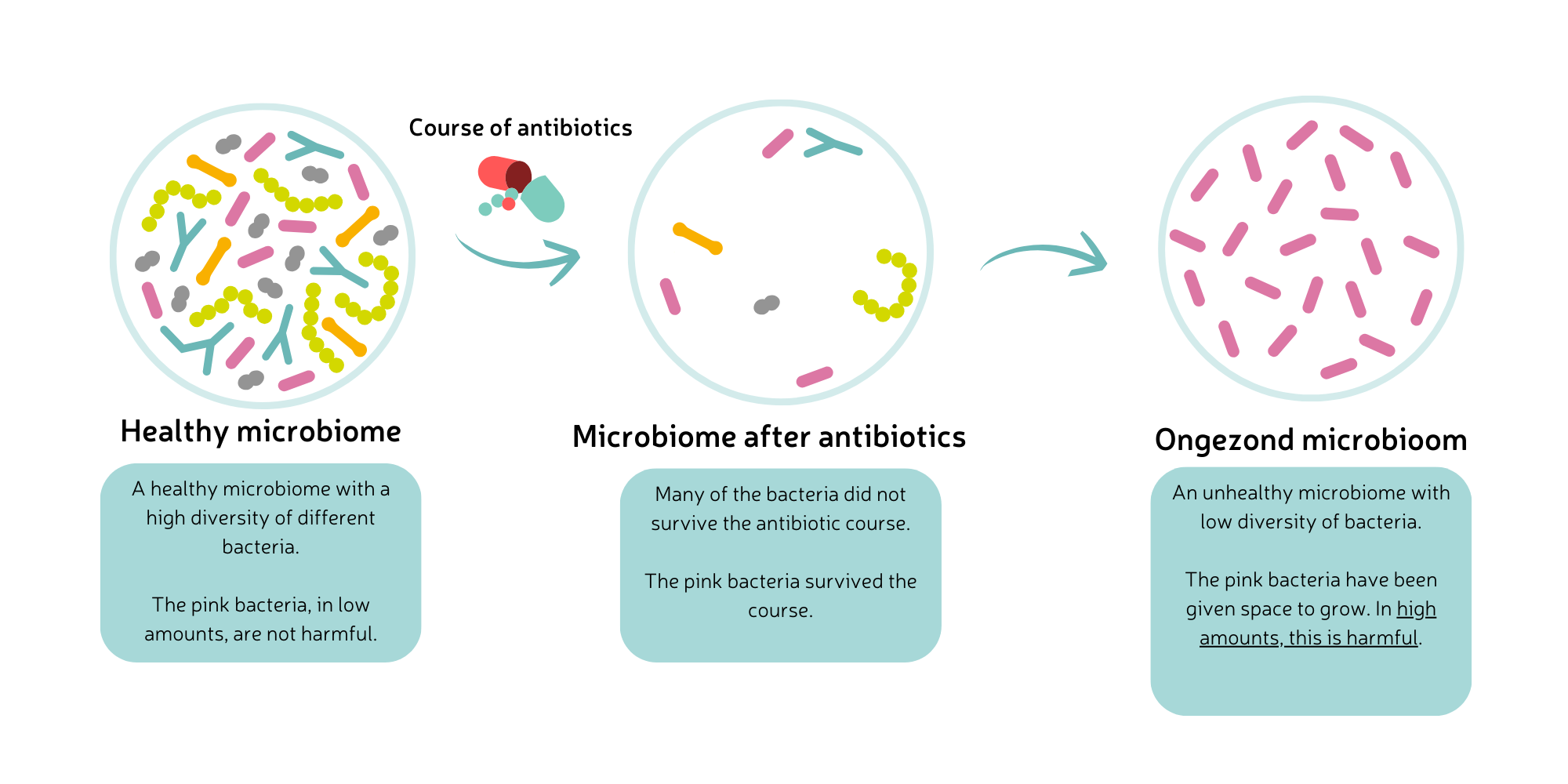

Additionally, there are five specific species known to cause health problems. The way they affect health varies by bacterium. For example, Clostridioides difficile naturally occurs in the intestines, but if it takes over (dominates) – such as after an antibiotic course – it can cause severe diarrhea and intestinal inflammation.

This situation explains how a specific species can begin to dominate the microbiome. An antibiotic course kills certain bacterial species (or inhibits their growth). Antibiotics do not differentiate between beneficial and unwanted bacteria. As a result, the microbiome can become unbalanced during and after an antibiotic course. The bacteria that remain can take the opportunity to grow faster. The notorious pathogen C. difficile does this, for example, leading to a C. difficile infection (CDI). The symptoms of CDI range from mild diarrhea and nausea to severe inflammation of the colon (colitis).

What will I see in my test results?

In your test report, you will receive scores for the amount of hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria, proteobacteria, and the five specific species. You will receive guidance and explanations on how you can reduce the scores (if necessary) using diet and lifestyle.

Also read: Do I have a disrupted microbiome?

Many bacteria are beneficial and help regulate various processes in your gut (and other organs) properly. These beneficial bacteria can roughly be divided into four groups: 1) keystone species, 2) gas-producing bacteria, 3) lactate-producing bacteria and 4) mucine-converting bacteria.

Gut bacteria that fall under the ‘keystone species’ category carry a lot of responsibility: they communicate with other organs (such as the liver), regulate nutrient absorption, and reduce inflammation. Keystone species do this by stimulating the growth and function of other beneficial bacteria. You can think of them as the general who leads and coordinates a group of soldiers (other bacteria).

Eubacterium rectale is a keystone species that produces a lot of butyrate - a growth food for other bacteria. In this way, E. rectale supports many beneficial processes in the gut.

Gas-producing bacteria ferment dietary fibers, releasing gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide. These are useful gases.

Dietary fibers are fermented in the large intestine by bacteria, which releases useful gases like carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen. Some bacteria use these gases for important body processes.

Although gas production is normal (and necessary), too much of it can cause digestive issues, such as bloating or excessive flatulence. Some gas-producing bacteria can even cause inflammation or disturbances in gut motility (peristalsis), which could play a role in IBS and IBD. The amount of gas depends on the type of fiber in the large intestine:

Both fibers are important! By combining them, such as oatmeal (soluble) with whole grains (insoluble), you slow down fermentation and reduce discomfort.

Lactate-producing bacteria produce lactic acid (lactate) during the fermentation of milk sugars. Lactate is useful because it lowers the acidity in the intestines, reducing the chances of pathogens growing and allowing beneficial bacteria to thrive. Lactate also serves as an energy source for other (beneficial) bacteria, including energy-producing species.

A low amount of lactate-producing bacteria can lower the growth and activity of energy-producing bacteria, disrupting many body processes. However, an excess of these bacteria is also undesirable.

An example is Lactobacillus, which naturally occurs in fermented foods like yogurt, sauerkraut, sourdough, and kefir. Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus also belong to this group of bacteria.

Mucine-converting bacteria play an important role in maintaining a healthy gut function: mucin is the main component of the mucus layer that covers and protects the intestinal wall. Certain bacteria specialize in breaking down mucin. This process contributes to a strong intestinal wall, prevents the entry of pathogens, and reduces the risk of inflammation.

When the amount of mucine-converting bacteria is low, the production of new mucus decreases. As a result, the mucus layer becomes older, weaker, and unable to properly protect against pathogens. A high amount of these bacteria leads to excessive mucus breakdown, and mucus production can't keep up. This makes the mucus layer around the intestinal wall thinner and more susceptible to inflammation. Therefore, a balanced amount of mucine-converting bacteria is important.

Examples of mucine-converting bacteria are Bacteroides vulgatus, Bifidobacterium longum, and Akkermansia muciniphila.

What will I see in my test results?

In your test report, you will receive scores for the amount of keystone species, gas-producing, lactate-producing, and mucine-converting bacteria. A deficiency of these bacterial groups can lead to constipation, bloating, or even intestinal inflammation. But an excess of these groups can also have unpleasant consequences – despite their beneficial activities. For example, you may develop stomach pain and excessive flatulence. In the report, you will find a detailed explanation of these groups, the bacteria that belong to them, and to what extent they are present. We give you tips on how to improve the scores. All for a healthy microbiome!

Finally, the report describes which enterotype you have.

The composition of gut bacteria in people can be divided into three groups, called enterotypes. You can compare enterotypes to blood types; each has its own composition with different characteristics.

Your enterotype is determined by the bacteria you encounter as a child, such as through diet. Later in life, your enterotype can change if you consistently eat different foods.

The microbiome of your gut is quite complex. It can be difficult to figure out where your specific issues are coming from. A microbiome test can help with that. In this article, you read what results you can expect from the test results. If you want to know how the MyMicroZoo microbiome test works exactly, read on this page.

Alcazar, M., Escribano, J., Ferré, N., Closa-Monasterolo, R., Selma-Royo, M., Feliu, A., ... & Balcells, E. (2022). Gut microbiota is associated with metabolic health in children with obesity. Clinical Nutrition, 41(8), 1680-1688 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.06.007

Frank, D. N., St. Amand, A. L., Feldman, R. A., Boedeker, E. C., Harpaz, N., & Pace, N. R. (2007). Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 104(34), 13780-13785 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706625104

Larsen, O. F., & Claassen, E. (2018). The mechanistic link between health and gut microbiota diversity. Scientific reports, 8(1), 2183 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20141-6

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K., & Knight, R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature, 489(7415), 220-230 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11550

Ni, J., Wu, G. D., Albenberg, L., & Tomov, V. T. (2017). Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation?. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 14(10), 573-584 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.88

Ott, S. J., Musfeldt, M., Wenderoth, D. F., Hampe, J., Brant, O., Fölsch, U. R., ... & Schreiber, S. (2004). Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut, 53(5), 685-693 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.2003.025403

Takeuchi, T., Kubota, T., Nakanishi, Y., Tsugawa, H., Suda, W., Kwon, A. T. J., ... & Ohno, H. (2023). Gut microbial carbohydrate metabolism contributes to insulin resistance. Nature, 621(7978), 389-395 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06466-x

Tilg, H., Moschen, A. R., & Kaser, A. (2009). Obesity and the microbiota. Gastroenterology, 136(5), 1476-1483 https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.030

KvK nummer: 65867637

Website door: Ratio Design

This website uses essential cookies to ensure correct functionality. In order to improve our site we can also use optional cookies.

More information