The gut bacteria test that gives you insight into your health

- Microbiome test kit

- 16S analysis

- Scientific insights

Learn more

about the microbiota

Last updated: 20-07-2025

People with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) often suffer from abdominal pain and bowel-movement problems. It is a chronic condition. If you occasionally experience bloating, flatulence, stool irregularities (diarrhoea or constipation) and/or abdominal pain, that does not automatically mean you have IBS. On this page you will read:

IBS is a common chronic disorder: an estimated five to ten percent of the Dutch population is affected. Complaints can vary greatly per person. One person mainly experiences abdominal pain and cramps, while another struggles with bloating or bowel-movement issues. Even in the same person, symptoms and their intensity can vary from day to day. But almost everyone with IBS shares one thing: diet influences the severity of the complaints.

A person with IBS shows no visible abnormalities. A diagnosis is therefore made on the basis of symptoms. This differs from intestinal diseases such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, where a diagnosis is made using a diagnostic test.

The most common IBS symptoms are abdominal pain, cramps, bowel-movement problems (diarrhoea, constipation), abdominal distension and bloating.

A GP or gastro-enterologist (MDL-arts) diagnoses IBS using the so-called Rome IV criteria:

Not sure? Then take the IBS test of the Dutch Digestive Diseases Foundation (MLDS) via this link. If the test suggests that you may have IBS, contact your GP for an official diagnosis.

Attention!

- Blood in the stool, fever, and sudden unexplained weight loss are not IBS symptoms. If you experience these, contact your GP immediately.

- If you are 50 years or older and suddenly develop IBS-like complaints, also contact your GP. Another disorder may be present, as the risk of serious intestinal diseases increases with age.

- In these cases it is not a good moment to do a microbiome test, because your microbiome will probably differ from its normal state.

Do you have IBS but have not yet managed to get rid of the complaints? MyMicroZoo is looking for people with IBS symptoms who are willing to follow the low-FODMAP diet and learn more about their microbiome. You may take a microbiome test with us free of charge. Read more about the study on this page.

IBS complaints can have various causes. The intestines may move too much, too little, or too spasmodically. The intestinal mucosa may also be oversensitive, triggering an immune reaction too quickly. The intestines can be more sensitive to stimuli such as food (visceral sensitivity), or there may be increased permeability, also known as a ‘leaky gut’.

The exact cause of these disturbances is not yet fully known. However, knowledge about IBS has increased in recent years. It is becoming increasingly clear that IBS is linked to a disturbed cooperation between the brain and the intestines. The two communicate closely in everyone: the intestines constantly send signals to the brain and vice versa, resulting in hunger, the urge to defecate or abdominal pain. This communication is unconscious. In people with IBS this interaction seems more sensitive or dysregulated, causing normal stimuli, such as food or gas formation, to be perceived quickly as painful or unpleasant.

Scientists have several theories about the origin of IBS. One suggests that IBS arises from damage to the intestinal wall, for example after an inflammation or infection, making the nerves in the intestinal wall sensitive. Another theory focuses on the balance of the microbiome. We discuss this further in the next chapter.

Hundreds of bacterial species live in the intestines. Many are beneficial, helping with bowel movements, vitamin absorption and immune activation. But unwanted bacteria can also be present, for example after an infection, medication (antibiotics) or a lot of unhealthy food. If the number of unwanted bacteria increases, they can disrupt the activity of beneficial bacteria. This can disturb bodily processes and cause pain, diarrhoea and/or constipation.

A microbiome test can help you discover which factors worsen your IBS complaints. After the test you receive a clear report showing which bacteria live in high or low numbers in your gut. For each species or group you read which useful functions they perform, or which adverse effects are linked to them. This gives you a clear picture of who ‘lives’ in your gut, allowing you to adjust your diet (such as a LOW-FODMAP diet) and lifestyle more precisely to reduce IBS complaints.

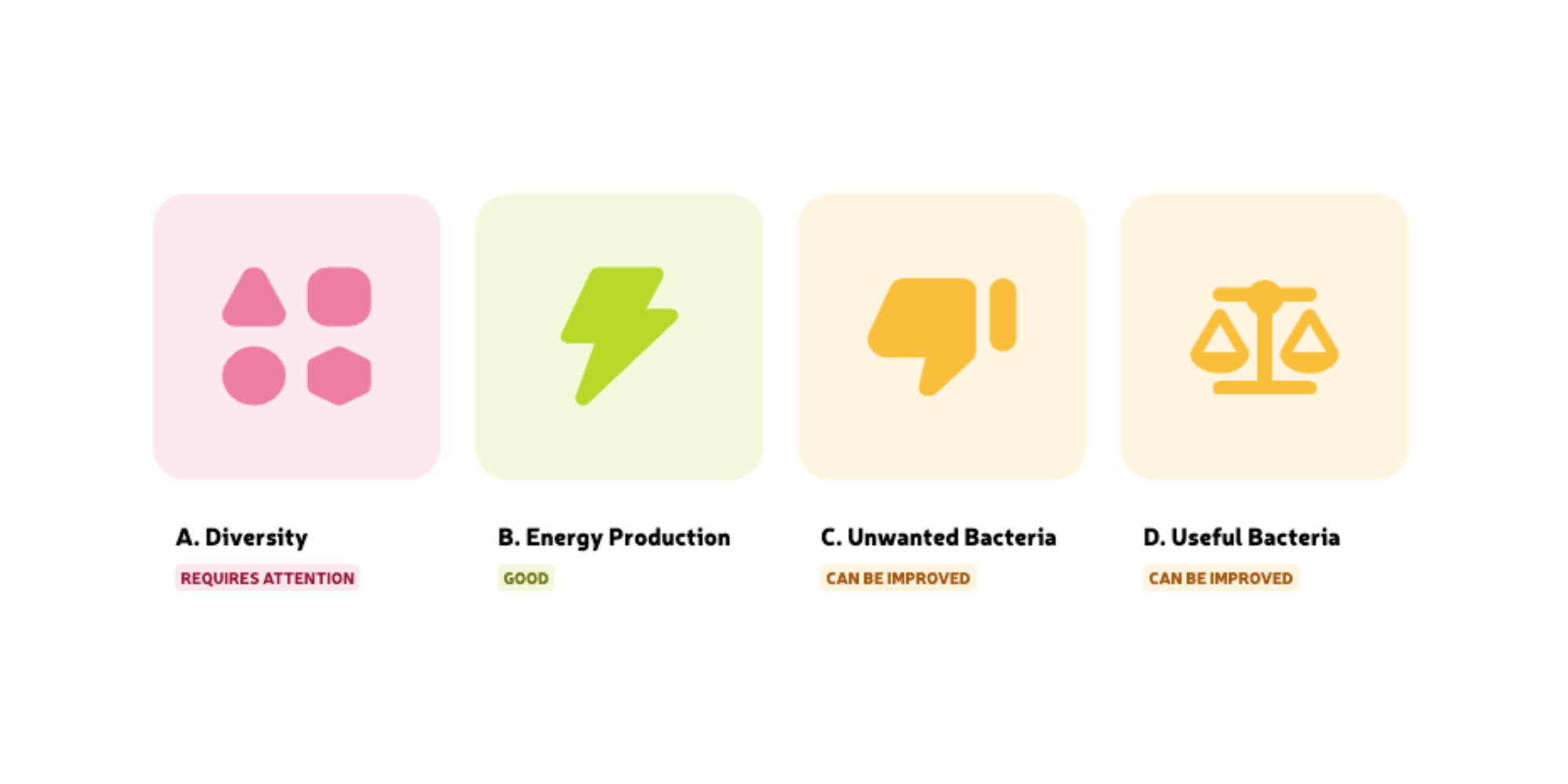

After taking a microbiome test you receive a report that explains your gut health step by step. The report has four main chapters (main scores) arranged according to what usually has the greatest impact on gut health. If you have been diagnosed with IBS, we recommend reading the report in a different order, because other bacterial groups influence your complaints more. This order is discussed below.

For everyone: first read the summary and the tips for improvement carefully.

For every pink and orange score we give practical tips to make your microbiome healthier. With a green score you receive an explanation on how to maintain this pattern.

Then read the report in this order if you have IBS:

Many gut bacteria can disrupt bodily processes and cause pain or other complaints, especially when these unwanted bacteria are present in high numbers. In the results report we divide them into three groups: sulphate-reducing bacteria, Proteobacteria and the specific species.

Finally, we group five other unwanted bacteria as the specific species—notorious bacteria. Each causes irritation, damage or inflammation in different ways. Bilophila wadsworthia, for example, produces large amounts of hydrogen sulphide that irritates the mucous layer of the intestinal wall. Fusobacterium is common and thought to produce small particles (lipopolysaccharides) that cause micro-inflammations, overstimulate our immune system and eventually cause severe intestinal inflammation.

Note that unwanted bacteria in low numbers (green) are not necessarily harmful. But when one or more of the above groups are highly present in your microbiome (pink or orange), they may be the cause of your gut complaints—rather than IBS.

If so, it is important to lower these bacterial scores. If complaints persist afterwards, another cause such as IBS is likely.

Some gut bacteria produce useful energy substances while processing dietary fibres. There are three forms: butyrate, propionate and acetate. Sufficient butyrate is very important (green) for proper intestinal function. It protects the mucous layer over the intestinal cells. A strong intestinal wall reduces the risk of inflammation. If this layer is weak (e.g. due to a lack of butyrate pink or orange), inflammations can occur and pathogens can more easily reach the intestinal cells, causing irritation, pain or disrupted bowel movements.

There are countless beneficial gut bacteria, each with an important function. The report discusses 14 of these species/groups. A low number of these bacteria (pink or orange) is not immediately bad or unhealthy, but you need enough beneficial bacteria (green) to maintain a diverse, balanced microbiome. They help curb the growth and activity of unwanted bacteria.

An example is the species that produces lactic acid (lactate). Lactate lowers intestinal pH slightly, stimulating many other beneficial bacteria and inhibiting unwanted ones.

A diverse microbiome (green) means many different bacterial species are present. Together they perform useful functions, making you more resilient against pathogens and reducing intestinal complaints. With lower diversity (pink or orange) a disbalance can develop: beneficial bacteria grow poorly, allowing pathogens to invade more easily and disturb processes such as digestion and bowel movements.

No, you cannot get rid of IBS; it is a chronic condition.

IBS medications can sometimes relieve cramps, diarrhoea or constipation. Always discuss with your (family) doctor which medication fits your complaint profile.

Experts advise adjusting diet and lifestyle as an ‘IBS treatment’ because this influences the microbiome composition and can therefore reduce complaints. A microbiome test gives insight into which areas of your diet and lifestyle need attention to relieve IBS complaints.

Carroll, I. M., Ringel-Kulka, T., Siddle, J. P., & Ringel, Y. (2012). Alterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology and motility, 24(6), 521–e248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01891.x

Chassard, C., Dapoigny, M., Scott, K. P., Crouzet, L., Del'homme, C., Marquet, P., Martin, J. C., Pickering, G., Ardid, D., Eschalier, A., Dubray, C., Flint, H. J., & Bernalier-Donadille, A. (2012). Functional dysbiosis within the gut microbiota of patients with constipated-irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 35(7), 828–838. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05007.x

Jeffery, I. B., O'Toole, P. W., Öhman, L., Claesson, M. J., Deane, J., Quigley, E. M., & Simrén, M. (2012). An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut, 61(7), 997–1006. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501

Kushkevych, I., LešÄÂÂÂÂÂanová, O., Dordević, D., JanÄÂÂÂÂÂíková, S., Hošek, J., VítÄ›zová, M., Buňková, L., & Drago, L. (2019). The Sulfate-Reducing Microbial Communities and Meta-Analysis of Their Occurrence during Diseases of Small–Large Intestine Axis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(10), 1656. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101656

Labus, J. S., Hollister, E. B., Jacobs, J., Kirbach, K., Oezguen, N., Gupta, A., Acosta, J., Luna, R. A., Aagaard, K., Versalovic, J., Savidge, T., Hsiao, E., Tillisch, K., & Mayer, E. A. (2017). Differences in gut microbial composition correlate with regional brain volumes in irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiome, 5(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0260-z

Liu, H. N., Wu, H., Chen, Y. Z., Chen, Y. J., Shen, X. Z., & Liu, T. T. (2017). Altered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver, 49(4), 331–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.01.142

Liu, Y., Li, W., Yang, H., Zhang, X., Wang, W., Jia, S., Xiang, B., Wang, Y., Miao, L., Zhang, H., Wang, L., Wang, Y., Song, J., Sun, Y., Chai, L., & Tian, X. (2021). Leveraging 16S rRNA Microbiome Sequencing Data to Identify Bacterial Signatures for Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Malinen, E., Rinttilä, T., Kajander, K., Mättö, J., Kassinen, A., Krogius, L., Saarela, M., Korpela, R., & Palva, A. (2005). Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. The American journal of gastroenterology, 100(2), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40312.x

Nagel, R., Traub, R. J., Allcock, R. J., Kwan, M. M., & Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H. (2016). Comparison of faecal microbiota in Blastocystis-positive and Blastocystis-negative irritable bowel syndrome patients. Microbiome, 4(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0191-0

Pittayanon, R., Lau, J. T., Yuan, Y., Leontiadis, G. I., Tse, F., Surette, M., & Moayyedi, P. (2019). Gut Microbiota in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome-A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology, 157(1), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.049

Prikkelbare Darm Syndroom Belangenorganisatie. (2022, November 29). Diagnose - prikkelbare darm syndroom Belangenorganisatie. https://www.pdsb.nl/diagnose/

Rajilić-Stojanović, M., Biagi, E., Heilig, H. G., Kajander, K., Kekkonen, R. A., Tims, S., & de Vos, W. M. (2011). Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 141(5), 1792–1801. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.043

Rangel, I., Sundin, J., Fuentes, S., Repsilber, D., de Vos, W. M., & Brummer, R. J. (2015). The relationship between faecal-associated and mucosal-associated microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 42(10), 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13399

Salminen, S., von Wright, A., Morelli, L., Marteau, P., Brassart, D., de Vos, W. M., Fondén, R., Saxelin, M., Collins, K., Mogensen, G., Birkeland, S. E., & Mattila-Sandholm, T. (1998). Demonstration of safety of probiotics -- a review. International journal of food microbiology, 44(1-2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00128-7

Sheikh Sajjadieh, M. R., Kuznetsova, L. V., & Bojenko, V. B. (2012). Dysbiosis in ukrainian children with irritable bowel syndrome affected by natural radiation. Iranian journal of pediatrics, 22(3), 364–368.

Su, Q., Tun, H. M., Liu, Q., Yeoh, Y. K., Mak, J. W. Y., Chan, F. K., & Ng, S. C. (2023). Gut microbiome signatures reflect different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Microbes, 15(1), 2157697. doi: https://doi.org10.1080/19490976.2022.2157697

Vich Vila, A., Imhann, F., Collij, V., Jankipersadsing, S. A., Gurry, T., Mujagic, Z., Kurilshikov, A., Bonder, M. J., Jiang, X., Tigchelaar, E. F., Dekens, J., Peters, V., Voskuil, M. D., Visschedijk, M. C., van Dullemen, H. M., Keszthelyi, D., Swertz, M. A., Franke, L., Alberts, R., Festen, E. A. M., … Weersma, R. K. (2018). Gut microbiota composition and functional changes in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Science translational medicine, 10(472), eaap8914. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aap8914

Wang, L., Alammar, N., Singh, R., Nanavati, J., Song, Y., Chaudhary, R., & Mullin, G. E. (2020). Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in the Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(4), 565–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.05.015

Zeber-Lubecka, N., Kulecka, M., Ambrozkiewicz, F., Paziewska, A., Goryca, K., Karczmarski, J., Rubel, T., Wojtowicz, W., Mlynarz, P., Marczak, L., Tomecki, R., Mikula, M., & Ostrowski, J. (2016). Limited prolonged effects of rifaximin treatment on irritable bowel syndrome-related differences in the fecal microbiome and metabolome. Gut microbes, 7(5), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1215805

Zhong, W., Lu, X., Shi, H., Zhao, G., Song, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Jin, Y., & Wang, S. (2019). Distinct Microbial Populations Exist in the Mucosa-associated Microbiota of Diarrhea Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Ulcerative Colitis. Journal of clinical gastroenterology, 53(9), 660–672. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000961

KvK nummer: 65867637

This website uses essential cookies to ensure correct functionality. In order to improve our site we can also use optional cookies.

More information